The singer-songwriter-author-filmmaker-artist-provocateur also becomes an octogenarian this month. He still means as much as ever, writes Keith Blackmore.

On January 8, 2016 – his 69th birthday – David Bowie released Blackstar. Two days later, his death from liver cancer was announced. Blackstar, completed in great secrecy during what Bowie knew were his final months, was literally his last word to his audience.

I am not alone among his legion of ardent, lifelong fans in considering it his greatest work. Blackstar is the creation of a man facing imminent death, with fear, courage and, this being Bowie, an elegant curiosity.

It is an often opaque and mysterious record, as much of his best stuff tends to be, but there, at the very end, is a final and uncharacteristically frank admission: “Seeing more and feeling less/Saying no and meaning yes/This is all I ever meant/That’s the message that I sent/I can’t give everything away.”

Bowie could write brilliant but readily understandable lyrics with the best of them, if he chose to (just listen to ‘Space Oddity’ or ‘Kooks’or ‘Life on Mars?’ or pretty much anything else on Hunky Dory). But once he had discovered the alluring power of being mysterious he never really gave anything away again – until that final song.

This was a lesson that Bob Dylan had learnt much earlier. Nothing about him was as it seemed, even from the start: not his name (Robert Zimmerman), nor his early claims to being the anointed disciple of the dying Woody Guthrie. And his youthful life before he came to New York was hardly the tough existence of the dusty bum who had been kicked out by his parents as he claimed: he came from a relatively comfortable home in Hibbing, Minnesota. But Hibbing was not far from Highway 61, the great road of the blues which young Robert was to travel both literally and figuratively to fame, fortune and artistic immortality.

Like Bowie, only more so, he has made his life his art. The songs, even the many great ones, are simply constituent parts of a greater work called Bob Dylan.

Naturally the arrival of his 80th birthday on May 24 is being feted far and wide with, among much else, a week-long series on BBC Radio 4, a tribute album by Chrissie Hynde, and at least four new books. Of these last, the best is probably the latest edition of No Direction Home, by Bob Shelton, who wrote Dylan’s first major review in The New York Times in 1961. Shelton, who knew Dylan well, died more than 20 years ago, but his book, first published in 1986, has been admirably updated and revised, first to mark the singer’s 70th and again now.

That updating is required is itself testimony to Dylan’s enduring energy and appeal. This last decade seemed for a long time to offer only small footnotes to the main text: a series of covers albums in which he offered, among other things, his take on songs that Frank Sinatra had made his own; a minor co-written album (Tempest); many, many concert dates around the world on the famous Never Ending Tour; and, of course, the Nobel Prize for Literature (sic).

But then, last year, just as the world entered lockdown, he released a new song, the 17-minute ‘Murder Most Foul’, containing a bleak but witty litany of how the world had gone wrong since the assassination of JFK in 1963, when Dylan’s career was beginning to fly. Delivered in what has regrettably become his trademark growl, the song could easily be heard as a broad summation of his life and career and was so doom-laden that it raised the possibility that it might be Dylan’s farewell.

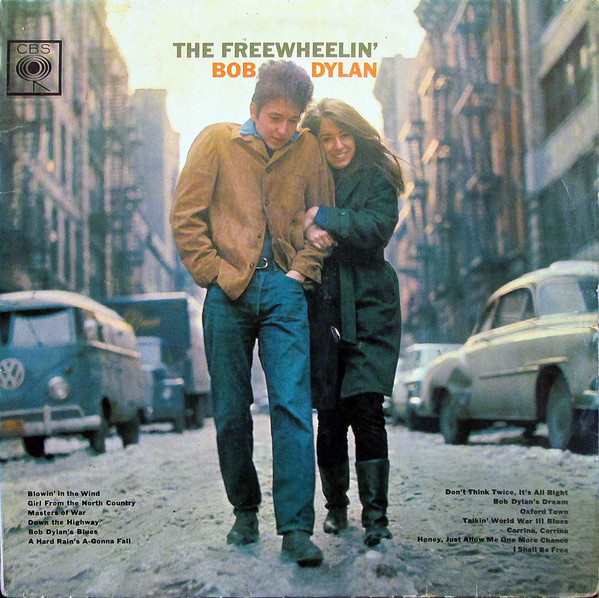

Happily, a few weeks later a full new album followed, featuring not only ‘Murder’ but also a series of brilliantly conceived and executed songs. Rough and Rowdy Ways was a major release by any standards, and gave Dylan the barely credible achievement of having produced at least one great album in five of the last six decades. No modern music collection would really be complete without The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), Highway 61 Revisited (1965), Blonde on Blonde (1966), John Wesley Harding (1967), Nashville Skyline (1969), Blood on the Tracks (1975), Desire (1976), Oh Mercy (1989), Time Out of Mind (1997), Love and Theft (2001), and now Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020).

Then there are the live albums and the sometimes thrilling “official bootleg” series, a collection of unreleased recordings which is nearing its 20th multi-disc volume (demonstrating that Dylan is both prolific and a poor judge of his own work).

And then there is the life itself. The sudden blooming of a songwriting talent that gave coherence to the swirling winds of protest in the 1960s; the brief but passionate relationship with Joan Baez; the sudden, post-Beatles switch from acoustic folk music to electric rock; the retreat from fame to married domesticity; the motorcycle accident; a bitter and painful divorce; and then a return to protest music with the Rolling Thunder Revue in the mid-1970s, followed by a short, unwelcome phase as a proselytising Christian.

All of this happened more than 40 years ago. But Dylan has kept on keeping on, “like a bird that flew” as he once wrote.

Much of the Dylan story has also been recorded on film. As early as 1965, he was famous enough – and sufficiently self-aware – to allow D.A. Pennebaker to make a memorable documentary about what turned out to be a historic tour of Britain that year.

Martin Scorsese has twice made films about him: the more or less straight documentary No Direction Home (2005), which told the story up to the motorcycle accident of 1965; and, in 2019, Rolling Thunder Revue. This last was ostensibly an editing of footage from the 1970s travelling musical circus of the title but it carried a subtitle: A Bob Dylan Story. For this was not really a documentary; rather a blend of frequently electrifying concert performances from 1976 mixed with interviews new and old, some of which were obviously fictitious.

And if the film’s most memorable sequence is of a transcendent Joni Mitchell making Dylan (and a host of other male stars) look decidedly earthbound, it is still hard to forget the image of Sharon Stone pretending to have been a teenage fan at one of the concerts. Scorsese’s film was just another part of the unfolding work: Bob Dylan, every bit as real and as fake as Dylan’s own (terrible) four-hour feature film Renaldo and Clara (1978), or his (excellent) autobiography Chronicles, Volume One (2004), parts of which also appear to be made up.

Increasingly in recent years, Dylan has turned to other art forms to tell the story. He has exhibited and sold paintings and drawings for eye-watering prices on both sides of the Atlantic.

Three years ago, he tried something else. The Halcyon Gallery in New Bond Street, London, staged the Mondo Scripto exhibition. Dylan had selected 60 of his greatest songs, and, using what looked like hotel stationery from an address in Dayton, Ohio, wrote out the lyrics in a surprisingly legible hand, illustrating each with a pencil drawing. Prices ran from £150,000 for originals down to £1,500 for prints, but it is difficult to believe that Dylan needed the money – he sold his publishing catalogue last year for an estimated $300 million.

His choice of songs was interesting, but there was something else: in some cases he changed the words. Take this example: Blood on the Tracks was a reaction to the break-up of Dylan’s ten-year marriage to Sara Lownds, and in one of its loveliest songs, ‘If You See Her, Say Hello’, he replays the past: “If she’s passing back this way/I’m not that hard to find/Tell her she can look me up/If she’s got the time.”

The Mondo Scripto version, handwritten more than 40 years later, reads: “If she passes back this way, and I sure hope she don’t/Tell her she can look me up/I’ll either be here or I won’t.”

Why would he make that lyric so much nastier? Why, for that matter, would he have changed the words to another masterpiece, ‘Tangled Up in Blue’, so radically?

The answer is, probably, just because he could. Dylan is no respecter of the sanctity of his own work, as anyone who has heard recent concerts can testify. His songs are moveable, malleable parts of one continuing narrative, no more nor less sacred than the made-up parts of the “documentaries”.

In the 60 years or so we have known him, Dylan’s appearance may have changed from the scruffy young hobo to the briefly handsome young rock star right up to the vaguely sinister figure crouched over his keyboard of recent concerts. The music has changed. Even those famous words have changed. “I contain multitudes,” he sang on his last album, quoting Walt Whitman.

If he ever had any peers they are all gone now. But Dylan remains, and if you look hard, you can still glimpse something of what the young David Bowie saw all those years ago.

“Hear this Robert Zimmerman/I wrote a song for you/about a strange young man called Dylan/with a voice like sand and glue/His words in truthful vengeance/could pin us to the floor/Brought a few more people on/put the fear in a whole lot more.”

Happy birthday, Bob. You’re going to make me lonesome when you go.

This article by Keith Blackmore was first published by Tortoise in May 2021. You can find out about a new kind of slow news at www.tortoisemedia.com