It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day.

I was out choppin’ cotton and my brother was balin’ hay…

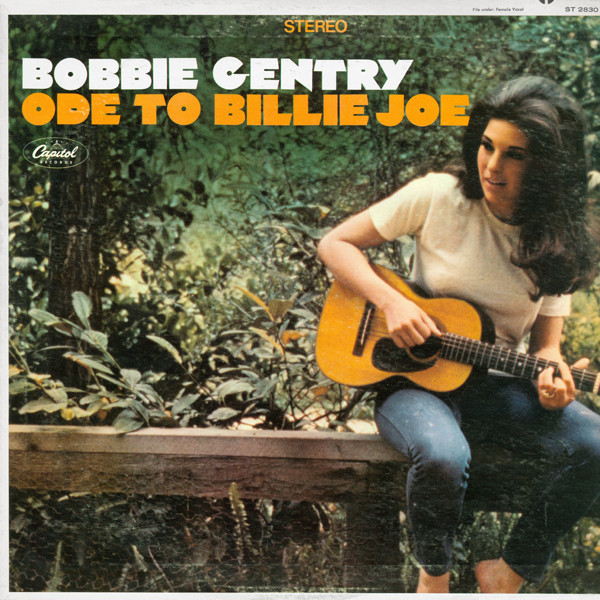

So begins one of the greatest, and most mysterious, hit songs of the Sixties, ‘Ode to Billie Joe’, recorded by Bobbie Gentry, a part-time swimsuit model from the wrong side of the tracks in Chickasaw County, Mississippi, in July 1967.

Three weeks later, ‘Ode’ was number one in the US Billboard charts, where it stayed for a month when such things meant enormous sales and a fortune for its unheralded performer. But the answers to the song’s questions – what did the unnamed narrator and Billie Joe MacAllister throw off the Tallahatchie Bridge, and why did he jump to his death on the morning the song begins? – have hung tantalisingly out of reach for more than half a century.

For all its mysteries, the song is a masterpiece of concision, evoking the hard, hot working life of the Deep South in a few simple phrases and establishing a mass of detail about a poor farming family in just five perfect verses.

It didn’t start that way. Gentry, then unknown, was invited by Capitol to record two self-written songs (‘Mississippi Delta’ being the other). She accompanied herself on guitar and, in just 40 minutes of studio time, delivered an 11-verse version of ‘Ode’. Record executives, scenting a hit, cut it from nearly eight minutes to four, excised six verses, added strings – and the rest, as they say, is pop history.

That brutal, brilliant edit created a multi-million selling masterpiece, but it also launched a frenzy of speculation about the story it told.

No one has plausibly suggested a real-life model for the events recounted in the song, but there are many theories about them. The most popular is that the narrator has had an abortion, or possibly even a baby (and, gulp, that’s what gets thrown off the bridge) but there are many variations, including ones that Billie Joe was black and the narrator white, or vice versa, at a time when interracial marriage was illegal in the South. (Mississippi did not actually repeal the interracial marriage legislation until 1987, although it had not been effective since 1967.) The infamous lynching by a mob of white men of Emmett Till, a young black visitor said to have insulted a white woman, occurred at Money, Mississippi – the site of the Tallahatchie Bridge – just 12 years before the song was recorded.

In 1976, a feature film, Ode To Billy Joe [sic], based on the song, was released to modest success. Billy Joe and Bobbie Lee (the narrator) are both white and their relationship is never consummated, but Billy Joe jumps off the bridge after a drunken homosexual encounter.

The original, uncut, 11-verse recording of the song has never surfaced. The one person who could explain it all is, of course, the artist herself. But Gentry has become as reclusive and elusive as Greta Garbo or JD Salinger. She gave the screenwriter of the film a single interview but told him she had no idea why Billie Joe had jumped off the bridge.

In many ways, Gentry is even more interesting than the characters in her greatest song. Born in Chickasaw County in 1942, her parents divorced almost immediately after her birth and she was raised by a combination of her grandmother, who is said to have sold a cow to buy her a piano, and her mother, who took her to California when she was 13.

In due course, Gentry worked there as a singer, a clerk and a fashion model to support herself while studying philosophy at the University of Southern California. Then she walked into that studio.

Her first album, also called Ode To Billie Joe, knocked The Beatles and Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band off the top of the Billboard charts. Her second, The Delta Sweete, though less commercially successful, is widely regarded as her masterpiece and was re-recorded last year in its entirety by the New York indie band Mercury Rev, with a version of Ode added as a final track.

Gentry went on to have other hits, her own BBC television series and a residency in Las Vegas. She became wealthy enough to be one of the founding owners of the Phoenix Suns NBA team. Three marriages came and went. But in 1978, without fanfare, she simply stepped out of the spotlight. She has lived privately ever since; most recently, it is said, in Memphis, less than two hours’ drive from where she was born and where her most famous song is set.

So back to that immortal song. Before her retirement from public life, Gentry gave few hints as to what happened to poor Billie Joe, perhaps sensing the power of the mystery.

But there is one real clue. In 1973, Gentry donated the original two pages of her handwritten lyrics to the University of Mississippi and, in 2006, one of them appeared briefly in an exhibition, Mississippi Matinee: The State and the Silver Screen. An entire, previously unseen and unheard first verse can be read, even though the first two lines have been crossed out. We hear about a whole new character, Sally Jane Ellison, and her disappearance since Billy Jo (as he is called in this draft) killed himself. If anything it leads us away from the familiar theories, suggesting, perhaps, a love triangle. The rest of the visible lyrics are pretty much as we know them and the second page is still unseen.

In any case, like Gentry, I’d prefer the mystery to lie undisturbed. Before she stopped talking about the song altogether, Gentry once told the Billboard columnist Fred Bronson: “The song is sort of a study in unconscious cruelty. But everybody seems more concerned with what was thrown off the bridge than they are with the thoughtlessness of the people expressed in the song. What was thrown off the bridge really isn’t that important.

“Everybody has a different guess about what was thrown off the bridge – flowers, a ring, even a baby. Anyone who hears the song can think what they want, but the real message of the song, if there must be a message, revolves around the nonchalant way the family talks about the suicide. They sit there eating their peas and apple pie and talking, without even realising that Billie Joe’s girlfriend is sitting at the table, a member of the family.”

That’ll do for me.

This article by Keith Blackmore was first published by Tortoise in June 2019. You can find out about a new kind of slow news at www.tortoisemedia.com